Malaria public policy and intervention

Problems while designing policies to combat malaria

To understand what policies can be implemented, we first need to understand what aspects of Malaria are “control-able.” Notice how this is different than other diseases because Malaria is vector-borne; this adds more layers to the question. Ways in which governments all over the world have tried to prevent malaria outbreaks can be broadly classified into these categories:

- One of them is to attack the parasite! Diseased population control: curing people who already have the disease so it doesn’t spread further. There is a slight issue with this because the disease-causing pathogen can continue living in the vector population and thus re-emerge in human populations.

- This brings us to the second classification, attack vector! Vector population control: try and control the amount of vector carrying the disease.

- The third broad classification prevents people from getting the disease, an interplay between human and vector control, minimizing interaction.

Malaria is thought to be a disease of the tropics. While it is true that Malaria does thrive in the tropics because of its mosquito vectors, Malaria was also a rampant problem in the US and Europe. Let’s look at what the US government implemented to try and control Malaria, both policies that did and didn’t work. The reason why I chose the USA as my case study was because it is a success story; in the present-day USA, Malaria can be considered eradicated.

Brief history of Malaria in the USA:

It was introduced in the USA with the advent of the slave trade in the 18th century. It was prevalent in the marshes and wet, low-lying areas, places like Carolina and Virginia, due to the presence of optimal breeding grounds. Incoming immigrants to the Americas started labeling sites as healthy and dangerous by the risk of catching Malaria, with Caribbeans being the worst and Florida and Carolina following up.

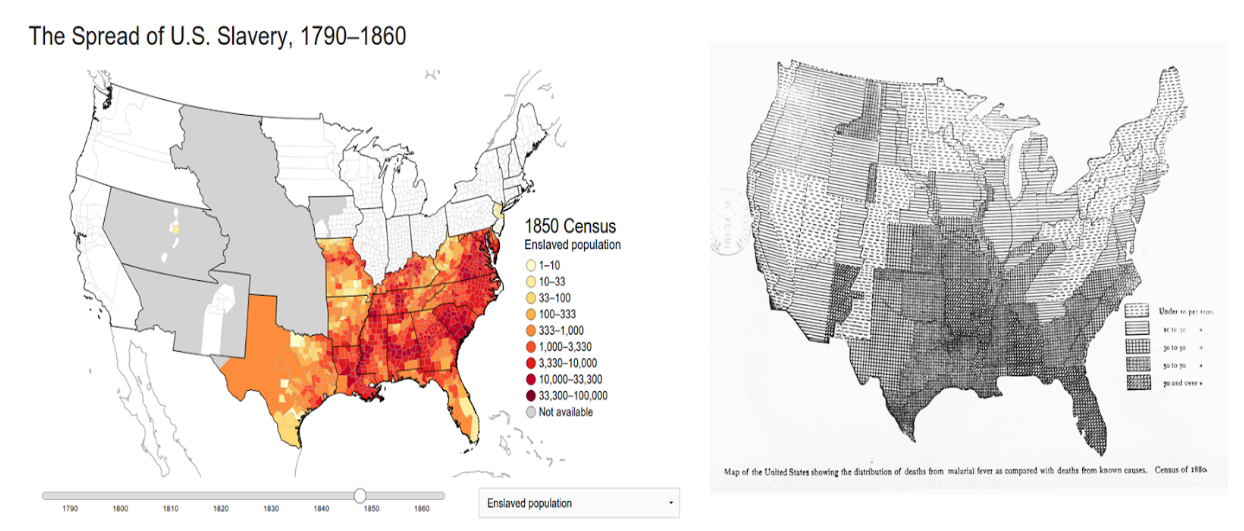

Also, because enslaved Black people had some tolerance to Malaria and white local laborers did not, the demand for slaves in these malaria-stricken areas increased. Here’s a map of malaria cases in 1883 next to slave populations in the 1860s

During World War 1, the soldiers training in the South started catching the disease. During the great depression in 1933, this worsened due to poor economic conditions, reporting well over a million cases! This is when deaths due to Malaria peaked the most.

Interventions

Settlement of Americans came with the added problem of malaria; new settlers had to not only find suitable habitable areas but also areas free of the disease. Around 1897, Ross discovered that mosquitos were the ones transmitting the disease. Once this was known, people started looking at ways to attack mosquitos directly. However, adult mosquitos are hard to get rid of, and hence, it was decided to attack mosquitos at the most vulnerable stage of their life cycle, their larval stage. As mentioned before, mosquitos lay their eggs in marshy stagnant water, which hatch into larvae and then into full-grown adult mosquitos. Therefore, one way to hit them where it hurts is to eliminate their breeding grounds, the marshy stagnant waters!

Let’s talk about William Gorgas, the chief sanitary officer (1904-1913) of the Panama Canal Commission and the “conqueror of Panama Canal fevers”. The construction of the Panama Canal was challenging because of the water logging and the mosquitos that came from it. Gorgas did the first practical demonstrations of disease eradication via anti-mosquito campaigns. His approach mainly included drainage, screening, hand-killing of adult mosquitos, and usage of quinine in the treatment of active cases. He even recruited children, paying them money per dead mosquito they “harvest.” Though his methods were very crude, he still successfully reduced the cases by as much as 80%! Gorgas’s method of malaria eradication was very labor and cost-intensive, the budget of which far exceeded that of the amount of money the southern states had for overall public health work. The South, titled by Roosevelt as “the Nation’s No. 1 economic problem”, was already poor, and Malaria contributed to this poverty. It’s hard to improve your financial condition when you have periodic and frequent anemia, fever, and chills. For example, Malaria peaked in August and September, which kept the farmers bedridden during the critical harvest days of the South’s primary agricultural produce, cotton.

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) took up Malaria in 1912 after just having finished their hookworm campaign, yet another disease that ravaged the rural South. Their first steps were to find the prevalence of the disease and hence help the places that need the most help. After just having finished their hookworm campaign, they were short on funds. Leaders of two communities, mill towns, whose economies were harshly affected by Malaria, approached the USPHS and asked them to organize malaria control programs in their communities. Major intervention strategies used in this area were to reduce mosquito presence through drainage and active usage of quinine, which was advocated by the USPHS workers who provided education about it.

This initial “attempt” was very promising, which led the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board (IHB) to collaborate with the USPHS; USPHS would provide personnel and their expertise in return for IHB funding projects in selected communities in the South. The scientists at IHB asked two main questions:

- What are the most effective yet cheap methods for malaria control?

- What methods are likely to gain continuous funding and public approval?

IHB planned on funding these only for a few years and hence had to find ways that the southerners could implement even after losing the external funding, so part of their project was involved in cooperation with local authorities and to teach the health officials how to manage the disease independently.

Hence, they began their research on malaria intervention strategies, testing two methods, mosquito control, and parasite control, separately in the Mississippi Delta. During 1916, they started their project in the delta, controlling mosquito levels by clearing and improving streams and ditches. The water bodies that could not be drained were sprayed with oil.

It was well known that quinine can alleviate the symptoms of Malaria. But only in 1916 did scientists start testing the efficacy of quinine in the treatment of Malaria. They started giving out quinine for free in malaria-stricken areas and found that it reduced malaria infections by 90%! Even though quinine was effective, they found that people stopped taking it for long enough due to its nasty side effects. Quinine was effective in interrupting the symptoms/ relieving symptoms, but the infection would come right back, and thus, it wasn’t the complete solution. Money was taken away from the IHB-USPHS project due to IHB moving their goals global and this is why funds were cut off from USPHS.

This brings us to public works projects, which started in the 1930s by Roosevelt to boost the economy by providing more people with jobs. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) began dolling out money nationwide, and several southern state health boards took advantage of this to launch drainage projects, with their motto being “a ditch in time saves quinine”; this simple adage guided all of the malaria work done in the mid-1930s.

This included projects to construct roads and channels; what is relevant to Malaria, however, areas containing water were drained (6,23,000 acres of watered area were drained). There was also an active fight against Malaria; the areas that could not be drained were sprayed with oil to prevent mosquitos from laying eggs and treated with Paris green, an arsenic-based compound that killed the larvae. These measures pushed down malaria numbers quite a lot, but Malaria was still present.

During WW1 the soldiers who trained in the south also face severe drawbacks due to malarial cases. And hence not to repeat the mistake, the government carried out malaria control in war areas, which received a lot of funding as well. The government cleared more than 623,000 areas of stagnant water and also sprayed open water bodies with insecticide oil and arsenic based compounds.

In 1933, the congress also passed the Agricultural Adjustments Act (AAA), which paid farmers to take land out of cotton production and encourages the use of more machinery. This lead to lot of people moving away from the south to the major cities in the north, which lead to mass removal from parasite load from the south.

All these did drive malaria cases down, but was not enough to completely eradicate it. Then came DDT (1945) and alongside this, Center for Disease Control (CDC) was launched in 1946. CDC sprayed house walls with DDT and provided window netting for free to everyone. Along with this, mass spraying of DDT was carried out all over America, which led to large-scale drop in mosquito populations. All of these combined led to the eradication of Malaria in the US in 1951!

Lot of what the US used cannot and should not be carried out in other countries. Usage of DDT and arsenic based compounds have severe impacts on the ecosystem, which can create more harm than good. Not only this but the US had sufficient funding to carry these out and this cannot be replicated in countries like India and Africa. But, advancements in technology and help from NGOs, like Melinda Gates Foundation, has greatly helped develop new strategies as well as refine existing ones to fit the needs of developing countries.

References

- Image credits

- File:United States Slavery Map 1860-sw.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

- The effects of the Works Progress Administration’s anti-malaria programs in Georgia 1932–1947 - ScienceDirect

- Ross and the Discovery that Mosquitoes Transmit Malaria Parasites.

- Margaret Humphreys - Malaria : Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States

- https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdfplus/10.2105/AJPH.38.7.931

- History - Elimination of Malaria in the United States (1947-1951)

- Eliminating Malaria in the American South: An Analysis of the Decline of Malaria in 1930s Alabama - PMC

- Should DDT Be Used to Combat Malaria? Scientific American

- Why a Malaria Vaccine Isn’t Available in the United States

- Some Lessons for the Future from the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955–1969)

- Ross and the Discovery that Mosquitoes Transmit Malaria Parasites.

- About Malaria - History.

- Malaria Films: Motion Pictures as a Public Health Tool - PMC

- Malaria - Our World in Data.

- Estimated number of malaria cases

- African disease statistics

- https://www.insectman.us/articles/mosquitoes/mosquito-origin-of-mosquitoes.htm

- The President’s Malaria Initiative and Other U.S. Government Global Malaria Efforts

- https://www.canadafreepress.com/2005/driessen052005.htm

- Malaria

- How Malaria Was Eradicated In The U.S.

- WPA (Works Progress Administration) - 1937